You’ve likely seen polygraph tests used in movies and on television shows, but how are these tests used in reality? In this blog, we’ll define polygraph tests, discuss their accuracy and use, explain why they’re not admissible in court, and help you understand your rights when it comes to taking these tests.

What Is a Polygraph Test?

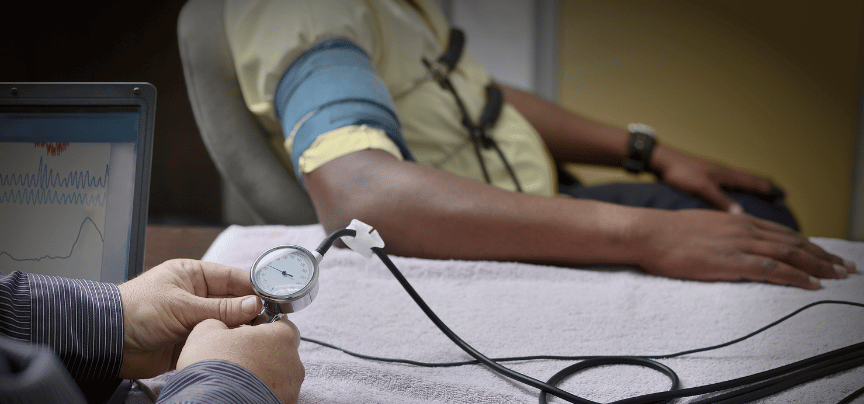

Polygraph tests record three types of physiological input from a test subject: cardiovascular activity, respiration, and skin conductivity. Before administering a test, the examiner will run a “pre-test” to prepare the person being questioned. The goal is for the pre-test is to help to eliminate false positives. For example, if the person is experiencing anxiety or doesn’t understand a question, the test may register a response that doesn’t necessarily reflect deception.

When it’s time to administer the test, the examiner places a blood pressure cuff, chest sensors, and finger electrodes (like those used at a doctor’s office to measure oxygen saturation) on the person being questioned to monitor activity in these different areas. While old-fashioned polygraph tests used mechanical pens that drew lines on a chart, modern polygraphs are computerized.

How Polygraph Tests Work

While the person being questioned is connected to the sensors, the examiner asks a series of questions, typically starting with name, the day of the week and similar questions to establish a response baseline when you’re not under stress. As the “real” test begins, questions will fall into one of two categories: control and relevant or material to the case at hand.

Control questions often involve past misbehavior but aren’t related to the crime or matter at hand. These might include:

- Have you ever broken a friend’s trust?

- Have you ever hurt someone?

- Have you ever shoplifted from a retail store?

Relevant questions correlate directly to the matter being investigated:

- Did you commit tax fraud in 2020?

- Did you steal from your employer?

- Did you use government grant funds for personal expenses?

The polygraph is built on the assumption that those being deceptive about the matter being investigated experience greater physiological responses to relevant questions as opposed to control, while those who are not deceptive demonstrate the opposite.

Are Polygraphs Accurate?

Polygraph tests have always been controversial, and the bottom line is they’re not allowed to be used as evidence in court. Investigators may also, legally, say you’ve registered deception when you haven’t to apply pressure and exert control during questioning.

According to the American Psychological Association, it might be more accurate to consider polygraph tests “fear detectors” rather than “lie detectors” since they tend to identify anxiety levels somewhat accurately in many people. However, medication, personality type and practice can allow someone to lie without demonstrating anxiety. The opposite is also true. Someone who is innocent may appear to be deceptive, when in fact medication, personality type and simply not responding well to being tested in general can influence reactions.

It is for these reasons that polygraph tests are not admissible as evidence in court.

Other Polygraph Uses

There are non-judicial settings in which polygraph tests are used. For example, a Probation and Parole Officer might test a subject on probation to gather a sense of whether that person is being deceptive about activities in which they’ve engaged. Private corporations, public and private agencies, and yes, even attorneys sometimes use these tests to gauge responses to questions.

The Bottom Line

Pressure is often applied in subtle ways to gain voluntary participation in a polygraph. Such as the test being used to “clear” you or remove you from suspicion, and, of course, if you have nothing to hide, you’d be willing to be tested.

Consult with your attorney before taking a polygraph. Your counsel will provide direction based on your case and circumstances. It’s important to understand your rights and not to feel pressured to comply with a test that, in the end, will never be used as evidence.